AUGUSTINE AND CULTURE SEMINAR PROGRAM

The Augustine and Culture Seminar (ACS) is a two-semester, first-year seminar course rooted in the Augustinian and Catholic intellectual traditions that prepares all students for success at Villanova and beyond.

ACS is an integral component of the first-year student experience. As an incoming student, you will be assigned to an ACS seminar as one of your first-semester courses and you will take a second ACS seminar course the following semester. In ACS, you will sharpen the practical and necessary skills of careful reading and clear writing. You will do this in community and conversation with your classmates who also live in the same residence hall with you. You will bridge the gap between the classroom and the campus, as you experience the exciting artistic and intellectual life of the University through “ACS Approved” cultural events.

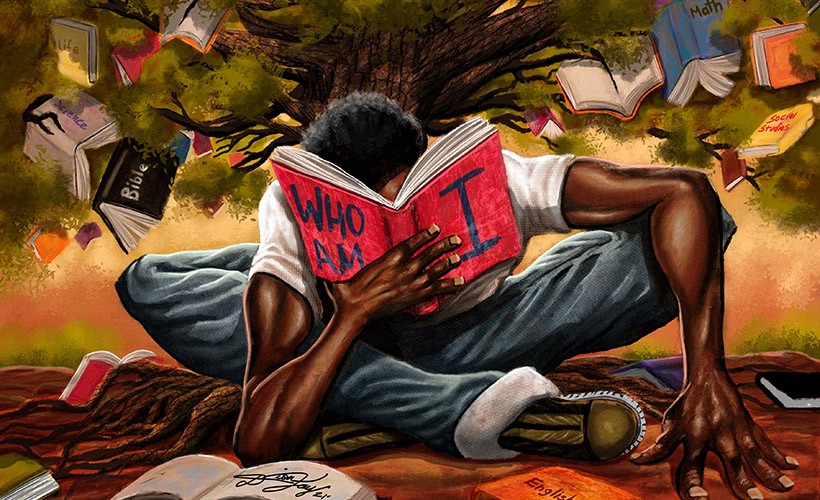

In ACS we cultivate what Pope Francis calls a “culture of encounter”: an environment in which we are passionate about learning about ourselves and others as we wrestle with thought-provoking works of human culture from ancient to modern times. Our model of inquiry is St. Augustine, the fourth century African bishop. ACS teaches you not only about Augustine but also how to be like him in the life-long pursuit of wisdom.

ACS is not a survey of traditions, but rather a humanistic inquiry into Augustine and his world (ACS1000: Ancients) and Augustine and our world (ACS1001: Moderns) — with the goal of encouraging each of us to ask, as Augustine did again and again, “Who am I?”

WHY ACS?

Your classmates in your ACS course will also be your hallmates in your dorm. All first-year students are housed by their ACS assignment, and some participate in selective learning communities.

All first-year students read St. Augustine’s spiritual autobiography “Confessions."