An Ecosystem

of Innovation

Drosdick Hall–a state-of-the-art building expansion–unites the College of Engineering in one location,

serving as a catalyst for cross-disciplinary innovation

As the sun rises on an early fall morning and its rays breach the walls that surround one of Drosdick Hall’s rooftop gardens, discovery awaits.

Bees search for a late-season snack on petite yellow flowers that shoot up from stonecrop and dangle on honeysuckle plants while the final pink blooms of sedum stretch onto a brick walkway, reaching for sunlight. Move too quickly and you might miss a pair of grasshoppers sunning themselves.

Given the beauty of this tranquil space, it may come as a surprise that it’s actually rainy days–not sunny ones like this day–that really make this roof shine. But as suggested by the name of the space–the Kinsley Living Laboratory and Rooftop Terrace–this is no ordinary garden. And what it tops is no ordinary building.

Built on–and for–Innovation

After more than a decade of planning and two years of construction, Drosdick Hall–the ambitious $125 million, 150,000-square-foot, state-of-the-art building expansion of the College of Engineering–opened its doors in fall 2024. This fall, the transformation was fully realized with the completion of additional lab and classroom renovations in the original wing of the building.

With more than 20 new research and teaching labs–totaling a 63% expansion of lab space–as well as instruction, work, study and office spaces, Drosdick Hall more than doubled the size of the College’s existing building.

Named for John G. Drosdick ’65 COE, a retired chairman and chief executive officer of Sunoco Inc., in recognition of $20 million in gifts in support of the expansion project, Drosdick Hall consolidates the College of Engineering under one roof. It brings together Chemical and Biological Engineering, Civil and Environmental Engineering, Electrical and Computer Engineering, Mechanical Engineering, and Sustainable Engineering, all of which had previously been spread across six buildings, along with the College’s newest discipline, Biomedical Engineering. The Richard K. Faris ’69 CE, ’70 MSCE Structural Engineering Teaching and Research Laboratory continues to serve the College from its dedicated location elsewhere on campus.

“Drosdick Hall is more than a building. It’s a launchpad for collaborative innovation,” says Michele Marcolongo, PhD, Drosdick Endowed Dean of the College of Engineering and professor of Mechanical Engineering. “By bringing together diverse disciplines in a shared, custom-designed space, we’re creating an environment where ideas can intersect and evolve into solutions that serve the greater good. Our students now have access to spaces that mirror the dynamic, team-based environments they will encounter in their careers, thereby equipping them not just with knowledge, but with the experience of working together to solve real-world challenges.”

Neighborhoods by Design

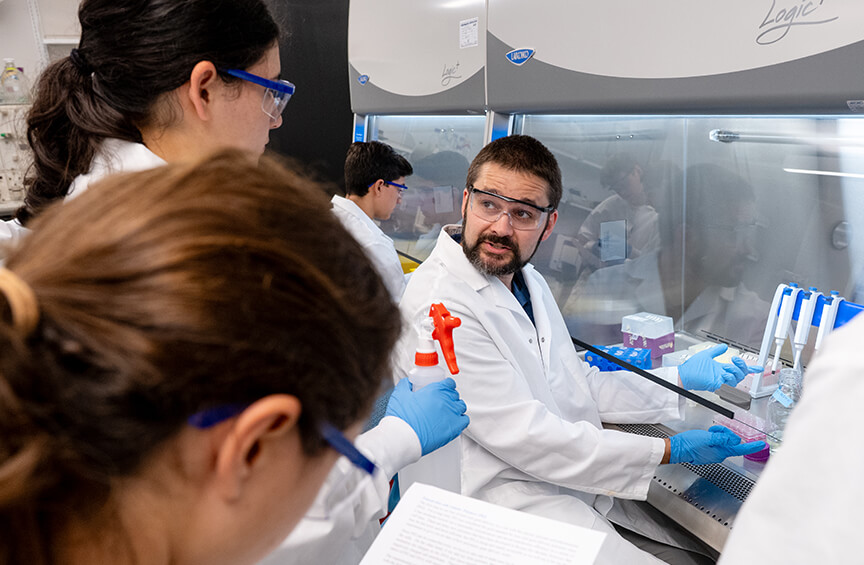

During the design phase, faculty played a central role in shaping the layout of Drosdick Hall. As chair of Chemical and Biological Engineering at the time, Noelle Comolli, PhD, associate dean for Faculty Affairs and professor of Chemical Engineering, joined other Engineering faculty and deans to identify professors working in related research areas and determine the best way to group them–not simply by department, but by shared research interests and equipment needs. The result was the creation of academic “neighborhoods.”

These innovative, thoughtfully designed areas foster connection and innovation around topical areas of research, including Advanced Energy, Intelligent Computing Systems, Biomaterials and Polymers, and Robotics and Autonomous Systems. By bringing together researchers from diverse disciplines, these spaces encourage shared discovery and accelerate cross-disciplinary advances.

“The labs are bustling. With up to 10 students working together in a single space, it feels like one large, collaborative lab group,” says Dr. Comolli, reflecting on the energy and interaction made possible by the academic neighborhoods.

Dr. Comolli reaps the benefit of this strategic clustering with her own work alongside Dean Marcolongo. Their research efforts converge around the study of arthritis. While they do not formally collaborate on a single project, their work shares a common focus and utilizes similar models.

Likening arthritis to the wear and tear of brake pads and fluid in a car’s braking system, Dr. Comolli emphasizes the importance of cartilage and lubrication around our joints. “Dean Marcolongo has designed a synthetic polymer that fills holes in the cartilage, and I have developed a drug-delivery system that administers steroids to help relieve inflammation and pain,” says Dr. Comolli. “We are exploring what other drugs might be added to promote regrowth of the tissue.”

Although their approaches differ–one structural and the other pharmaceutical–their shared lab space and equipment have enabled their students to work closely together, exchanging expertise and supporting each other’s research. Dean Marcolongo and Dr. Comolli also serve on the graduate thesis committees for each other's students, further strengthening the academic and mentoring ties between their groups.

Supportive Spaces for Advanced Scholars

The benefits of academic neighborhoods extend beyond the faculty to the graduate students. Thoughtful efforts during the design of Drosdick Hall aimed to ensure that master’s and doctoral students would feel just as integrated into the academic community as undergraduate students. One of the key outcomes of this planning was the creation of dedicated desk space for graduate students connected to each lab, along with amenities such as graduate lounges and private lactation rooms for parents, creating a supportive and inclusive environment.

“The design of Drosdick Hall is great. The large open areas downstairs and shared grad spaces allow ad hoc conversations with other students about their research or positions in the program,” says Peter Rokowski ’13 CLAS, ’15 MS, a PhD candidate in Computer Engineering. “We can discuss challenges or successes with publishing and research without having to specifically plan for it. Lately I’ve run into a few friends in different programs who were able to give me advice regarding the process for my dissertation proposal.”

This commitment to collaboration was further reflected in summer meetups that brought together all principal investigators and their graduate students for weekly sessions focused on scholarly exchange. Organized by Gabriel Rodriguez Rivera, PhD, and Laura Bracaglia, PhD–both assistant professors of Chemical Engineering–each session featured student-led presentations, with the first half dedicated to individual research projects and the second half offering technical tips on using shared lab equipment.

These gatherings helped students become more familiar with available tools–such as high-performance liquid chromatography–and encouraged peer-to-peer support, fostering a dynamic atmosphere where both students and faculty benefited from the diverse expertise within the lab.

“Graduate students benefit from access to equipment across multiple labs–not just their own–which helps them gather more data and strengthen their research,” says Dr. Rodriguez Rivera. “These collaborative exchanges of information encouraged students to share training, expertise and techniques, making their work more robust and well rounded. We want students to feel empowered to pitch new ideas to faculty, and daily lab interactions can lead to entirely new directions in research.”

Building as a Teaching Tool

As much as there is for students to learn in the building, there is also a substantial amount for them to learn from the building–no surprise given that it is the ninth LEED-certified building on campus. Developed by the US Green Building Council, the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) framework promotes healthy, highly efficient and cost-effective buildings worldwide, designed for the long term. Drosdick Hall represents not just smart and holistic design, but also the University’s commitment to shaping a more innovative and resilient world.

Drosdick Hall sets a new standard for sustainable design in laboratory buildings, which traditionally demand high energy use due to constant air circulation and exhaust systems. To mitigate this, the building features a highly efficient heating and cooling system that adjusts in real time based on occupancy and carbon dioxide levels, ensuring energy is used only where and when it’s needed. Chilled beams filled with cool water and radiant heaters near windows fine-tune the indoor climate, targeting specific zones rather than conditioning the entire space.

Sophisticated LED lighting throughout the building consumes less energy and emits less heat than fluorescent fixtures, reducing the cooling load. The lighting system also maximizes “daylight harvesting,” automatically dimming or turning off when natural sunlight is sufficient. If shades are lowered to block heat, sensors adjust the brightness accordingly, while occupancy sensors ensure lights are on only in active areas. Additionally, individual lamps and fans built into desks and shared tables allow occupants to address their comfort needs without affecting the entire room.

Advanced window glazing allows natural daylight to enter while blocking infrared and UV rays that contribute to overheating, reducing the need for artificial cooling. Upgraded exterior insulation exceeds building code requirements by more than double, significantly improving thermal efficiency.

These integrated strategies collectively reduce the building’s carbon footprint by the equivalent of five acres of mixed hardwood forest–an achievement that underscores Drosdick Hall’s role as a model for sustainable engineering and responsible design.

“When students see sustainable practices integrated in their daily lives during their education, those practices become second nature and carry forward into their career,” says Director of Sustainable Engineering Bridget Wadzuk, PhD, ’00 COE, who is also the Edward A. Daylor Chair in Civil Engineering and director of the Villanova Center for Resilient Water Systems. “Drosdick Hall itself is teaching students how to build a more sustainable, resilient building. The green roof is a primary example of that.”

“ When students see sustainable practices integrated in their daily lives during their education, those practices become second nature and carry forward into their career. ”

- Bridget Wadzuk, PhD, ’00 COE

The Gold Standard in Green Roofs

Drosdick Hall stands as a testament to the University’s leadership in sustainable innovation, and the green roof is one of the latest milestones in a 25-year commitment to transforming the campus into a model for stormwater management and environmental stewardship.

Beneath the soil that is spread across three areas on the roof and ranges in depth from a few to 20 inches lie instrumented systems to collect and monitor climate and soil moisture data. The information will provide innovative resources for both teaching and research.

Much more obvious than the buried instrumentation is a 500-gallon storage tank. “The storage tank on the roof serves two key purposes: It captures rainwater to prevent it from entering the drainage system during a storm, and it stores that water for future irrigation,” says Dr. Wadzuk. “We’re keeping the water where it landed, rather than letting it move downstream.” The stored rainwater is then reused to irrigate the roof’s vegetation, reducing reliance on potable water.

As for the water that does move downstream? Naturally, there’s a plan for that as well.

Drosdick Hall incorporates nature-based solutions to reduce stormwater runoff, which can pollute waterways and strain treatment systems. Rain gardens around the building funnel stormwater into temporary ponds that gradually recede, while a landscaped swale near the entrance slows water flow to promote infiltration. Underground, four 10,000-gallon cisterns collect rainwater, which is filtered and reused for flushing toilets in bathrooms that also boast low-flow faucets. These measures save approximately half a million gallons of water annually. Taken together, these strategies make Drosdick Hall not just a model of sustainable engineering, but a dynamic space for innovation and education.

The Power of Partnerships

One floor down from the Green Roof, Qianhong Wu, PhD, professor and chair of Mechanical Engineering and director of the Cellular Biomechanics and Sports Science Laboratory, works to advance his concussion research–just one of his multiple areas of focus.

Using his “smart brain” invention–a first-of-its-kind model that mimics the human head and consists of a transparent skull, simulant brain matter, supporting structure and watery cerebrospinal fluid that surrounds the brain–Dr. Wu studies how brain matter moves inside the skull during impact. Full instrumentation, including high-speed cameras, pressure sensors, accelerometers and displacement sensors, captures the flow and pressurization of cerebrospinal fluid during simulated trauma. This enables Dr. Wu and his team to measure the motion and deformation of brain matter and better understand brain injuries and how to prevent them.

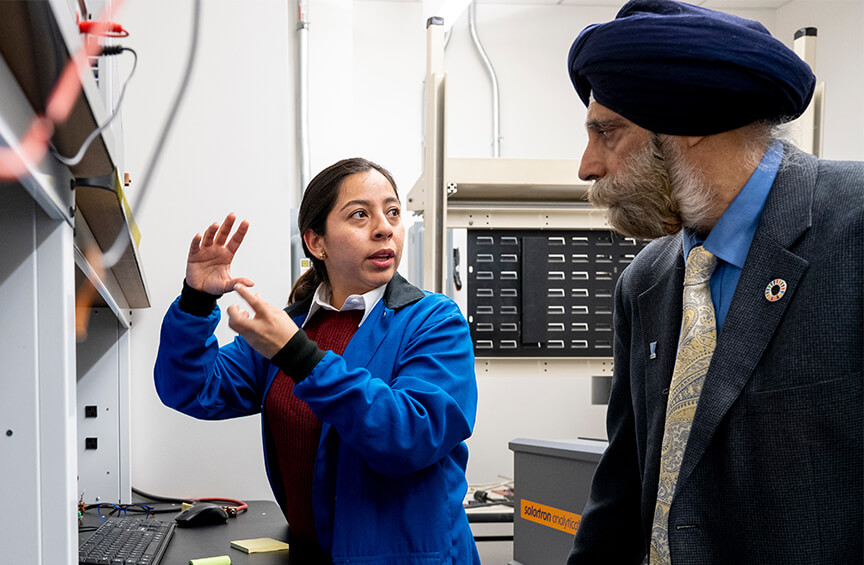

The groundbreaking research, which this year was awarded its third patent, drew the attention of Xun Jiao, PhD, associate professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering. A data scientist who has expertise in machine learning, Dr. Jiao approached Dr. Wu and offered to help.

“Artificial intelligence has been and can be used to process and understand imaging, so I knew it could be beneficial here,” says Dr. Jiao.

Now the pair have a joint project that uses hybrid diffusion imaging and AI to improve the understanding of traumatic brain injury. By converting MRI data into numerical values using diffusion tensor imaging, they apply machine learning to analyze damage and correlate it with different treatment outcomes. This approach helps identify which treatment options are most effective, moving beyond anecdotal evidence to data-driven insights.

The project, which has led to published papers in Frontiers in Neuroscience and AI in Neuroscience, was one of the first to fall under the College’s Sports and Performance Engineering initiative, which aims to leverage technology to enhance human performance and enable people–athletes and nonathletes alike–to live their best lives.

For Dr. Wu, the move to Drosdick Hall has opened up exciting possibilities. The expanded lab space and proximity to other departments have transformed the way he works. “I get the chance to meet so many people from different fields. We see each other, we talk to each other, and that leads to collaboration,” he says. What’s more, his team can conduct more advanced and integrated experiments.

(More) Cool Tools of Drosdick

Engineers thrive on solving problems with precision and creativity—and that starts with the right tools. Drosdick Hall is packed with cutting-edge instruments that power innovation and research. Here are just a few of the high-tech highlights found throughout the building.

The Microfluidic Cell Sorter can look at an individual cell—in a population of thousands—and determine its properties and sort it based on those properties.

The Oxford-WITec Confocal Raman Microscope uses laser light to create unique chemical fingerprints for materials, allowing Villanova researchers to study fuel cells in action, detect PFAS and microplastics in stormwater, and develop new materials for sensors and medical devices.

The ARAMIS High Speed 3D Digital Image Correlation System creates a three-dimensional map of strain and stress on a material—without touching it. At Villanova, it's used to simulate concussion effects, study brain-like material deformation during Deep Brain Stimulation procedures used to treat Parkinson’s disease and analyze artificial blood vessels to better understand atherosclerosis and other cardiovascular conditions.

The High-Fidelity Driving Simulator features a real car setup surrounded by screens that re-create driving conditions and then uses sensors that track eye movement, heart rate and brain activity, allowing researchers to study how drivers react to distractions, road design or new technologies such as self-driving cars.

Using the Multimodal Transportation Simulator in Virtual Reality, participants step into a realistic 3D city environment, where they cross streets, ride bikes and interact with autonomous vehicles, helping researchers—with a blend of engineering and psychology—to understand how people feel, move and make decisions in different transportation settings.

A Hub for Hydrology Innovation

On the lowest level of Drosdick Hall, the Giunco Family Hydraulic and Sediment Dynamics Lab is home to a research instrument unlike any other in the world: a 50-foot glass-sided hydrology flume suspended inside a stainless-steel frame. Installed through a National Science Foundation grant, this one-of-a-kind flume can tilt, recirculate sediment, generate waves, and precisely control water flow and height–all of which enable researchers to simulate real-world water scenarios.

“We have two types of experiments we can do with the flume: one representing rivers in the natural environment, and the other representing the urban environment and stormwater infrastructure,” says Virginia Smith, PhD, associate professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering and associate director of the Villanova Center for Resilient Water Systems.

“While there are other flumes in the world that can circulate sediment, what makes this one truly unique is that we are able to place green stormwater infrastructure [GSI] directly into the flume,” says Dr. Smith. “No one else has these sediment baskets. It allows us to design infrastructure that’s more resilient.”

Just over a year in operation, the flume is already hosting three active projects, each involving a collaborative team of faculty that spans multiple Engineering disciplines and research areas, including GSI, sediment behavior and pollutant pathways, all of which are critical issues in both natural and urban environments.

The flume's impact even extends beyond campus, contributing to ongoing regional efforts such as stormwater management projects that use GSI—rather than traditional methods—to treat highway stormwater runoff. “Instead of sending the runoff to an energy-intensive treatment plant, we’re processing it all just using plants and using GSI,” says Dr. Smith. Experiments in the flume directly inform the design and effectiveness of these systems.

“The flume allows us to work across disciplines and span so many different types of fields and research, empowering Villanova engineers to push the boundaries of stormwater research,” says Dr. Smith. “The acquisition of groundbreaking instruments such as this, coupled with the expertise of the University’s accomplished Engineering faculty, solidifies Villanova’s position as a national leader in innovative, impactful water systems research.”

“ I get the chance to meet so many people from different fields. We see each other, we talk to each other, and that leads to collaboration. ”

- Qianhong Wu, PhD

Engineering the Future

As the sun sets over Drosdick Hall, it illuminates more than plants and pollinators. It shines on a new era of Engineering at Villanova. From its living laboratory above and down through its nearly two dozen other laboratories, truly every inch of the facility is designed to spark discovery. Just as bees and grasshoppers quietly go about their work in the rooftop ecosystem, students, faculty and staff inside are engaged in a vibrant, interconnected pursuit of knowledge that transcends traditional academic boundaries.

“The creation of Drosdick Hall bolsters Villanova’s growth in national stature and research output,” says University Provost Patrick G. Maggitti, PhD. “Transforming and increasing academic spaces with an emphasis on STEM areas is built into the University’s Rooted. Restless. strategic plan. The expansion of the College of Engineering building moves this initiative forward and ensures that future generations of Villanova engineers will continue to collaborate and innovate.”

As the University continues to invest in spaces that support its academic mission, Drosdick Hall stands as a clear example of how thoughtful design can enhance learning, research and community. ■

DID YOU KNOW?

During excavation for Drosdick Hall, engineers encountered gneiss–one of the world’s hardest rocks–and needed to get creative. Unable to drill as deep as planned in spots, they cleverly adjusted the ceiling height in part of the basement to work with geology rather than against it.

NEXT IN FEATURES

Is CPR Always the Right Answer?

Villanova experts review the latest developments in cardiopulmonary resuscitation